Hey everyone! Welcome back to my blog series. Recently, I’ve been dedicating time to my basic my-shell project, where I’m working on implementing a shell in C++. While doing so, I got stuck in adding piping functionality. In this blog, I will be explaining the piping process. So, let’s start with the fundamental question, what is piping?

A mechanism or a process through which the output of a command is used as an input for another command. In simpler words, it involves the chaining of the commands, creating a pipeline through which data flows. Pipe operator is denoted by |. Commands in the pipeline are executed sequentially. Pipe has Queue data structure and behaves like FIFO.

How piping works

- A separate process is created for each command in the pipeline using

fork()syscall. - A commiunication channel is setup through pipe (

|) between the consecutive commands. - Pipe is unidirectional in nature.

pipe()syscall creates a pair of file descriptors:one pointing to the read end and one to the write end. - Each process in the pipeline redirects its standard input (

stdin) to read from the read end of the pipe and its standard output (stdout) to write to the write end of the pipe. - As the command is executed, it reads data from the previous command through pipe, processes it and writes the output to the next command in a sequential manner

Implementation

Let’s understand how we can implement this mechanism in our shell. First of all, let’s see how shell works in a simple way. It first takes input as a string, then it parses the input into arguments and thus executes the command with help of fork-exec model.

What if when pipe is used, for e.g. command1 | command2 | command3. There are multiple commands now, so each command is now need to be parsed and count the number of pipes used.

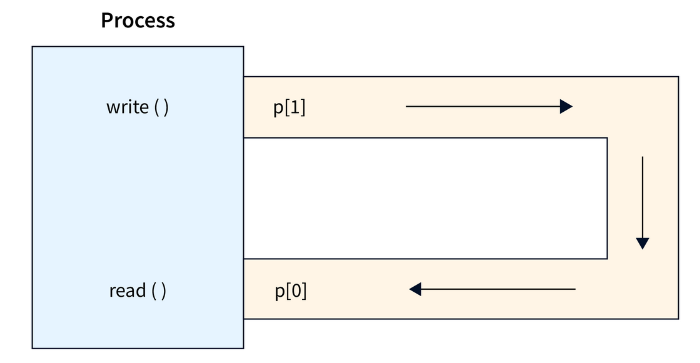

A pipe() syscall gives two file descriptors: pfd[0] for read, and pfd[1] for write

int pipes_count = commands.size() - 1;

int pipefds[pipes_count * 2]; // array to hold file descriptors for pipes

for (int i = 0; i < pipes_count; i++) {

if (pipe(pipefds + i * 2) == -1) { // initialize pipe

perror("pipe");

return 1;

}

}pipe(pipefds + i * 2): this intialises the two consecutive file descriptors. When i is 0, it initializes pipefds[0] and pipefds[1]. Hence, we have created all the required pipes before forking the processes. Now, fork the processes. Each command will run in its own child process.

So, we have input: command1 | command2 | command3. There are two pipes and three commands. There will be four file descriptors, two for each (one for read end and one for write end).

for(int i=0; i< commands.size(); i++)

{

pid_t pid= fork();

if(pid==0) // child process

{

if (i > 0) { // redirect input from the previous pipe

if (dup2(pipefds[(i - 1) * 2], 0) == -1) {

perror("dup2");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

}

if (i < commands.size() - 1) { // redirect output to next pipe

if (dup2(pipefds[i * 2 + 1], 1) == -1) {

perror("dup2");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

}

for (int j = 0; j < 2 * pipes_count; j++) { // Close all pipe file descriptors

close(pipefds[j]);

}

vector< string> args = parsing_string(commands[i]);

vector< char *> cargs;

for (const auto &arg : args) {

cargs.push_back(const_cast< char *>(arg.c_str()));

}

cargs.push_back(nullptr);

if (execvp(cargs[0], cargs.data()) == -1) {

perror("exec");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

} else if (pid < 0) {

perror("fork"); // Error in forking

return 1;

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < 2 * pipes_count; i++) {

close(pipefds[i]);

}Wehn i==0, child process for command1 will be forked. It will write to Pipe1. stdout of command1 will be redirected to Pipe1 write end, dup2(pipefds[1], 1);

When i==1, child process for command2 will be forked. It reads from pipe1 and writes to pipe2. dup2(pipefds[0], 0); : redirects stdin of command2 to Pipe 1’s read end and dup2(pipefds[3], 1);: redirects stdout of command2 to Pipe 2’s write end.

When i==2, child process for command3 will be forked. It reads from Pipe 2. dup2(pipefds[2], 0) redirects the standard input of command3 to the read end of Pipe 2.

After setting up the necessary redirections using dup2, the child process closes all pipe file descriptors. This is because once dup2 has duplicated the file descriptors to stdin (0) and stdout (1), the original pipe file descriptors are no longer needed by this process.

After forking all child processes, the parent process closes all pipe file descriptors. This is important because the parent process does not need to use these pipes itself.

Closing the file descriptors prevents the resource leakage and ensures the proper functioning of the pipeline.

Thus, we have reached at the end of this blog. Thank you for your attention, hope you like it.

References

- https://www.scaler.com/topics/pipes-in-os/

- https://github.com/Sl4y3r-07/my-shell

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/63544779/how-is-pipe-uni-directional-when-we-get-two-file-descriptors-by-calling-pipe-f

- https://inst.eecs.berkeley.edu/~cs162/fa21/static/dis/dis2.pdf